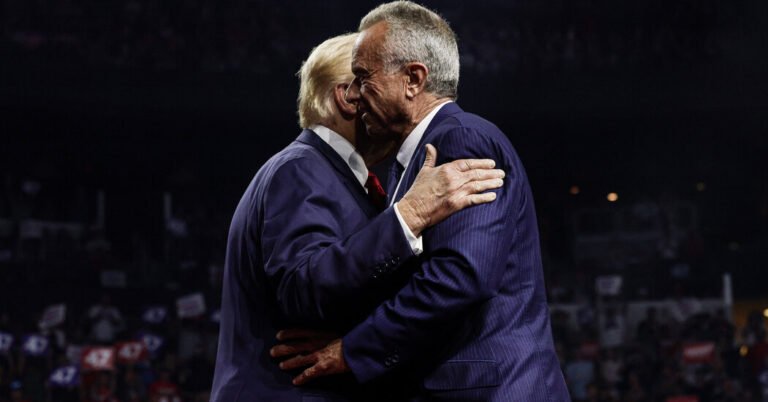

Last week, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., once a prominent figure of America’s environmental movement, suspended his independent run for the White House and endorsed former President Donald Trump.

On its face, the announcement seemed jarring. Trump has called climate change a “hoax” and, during his time in office, worked to unravel more than 100 environmental policies and regulations. Kennedy, who worked for years as a lawyer fighting against polluters, had claimed he would have been the “best environmental president in American history.” Most experts consider Trump’s presidency to be among the most punishing to the environment in recent history.

In April, as Lisa Friedman reported, nearly 50 of Kennedy’s former colleagues at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit group, took out full-page ads in a number of newspapers in swing states to ask him to “honor the planet” and withdraw from the race because they feared his candidacy could help Trump.

So how did Kennedy end up here?

Kennedy’s campaign didn’t respond to my questions about how he squares his life’s work with his support for Trump. But Kennedy’s announcement didn’t seem to surprise those who have worked with him or followed his environmental career.

Today I want to explain why.

Kennedy’s environmental record

Kennedy, 70, is a son of the former attorney general and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, and a nephew of former President John F. Kennedy.

Kennedy loved animals and nature as a child, but his work on environmental issues started in the 1980s when he was required to do community service after being sentenced to probation in connection with heroin charges, according to a recent profile in The New Yorker. That’s when he started volunteering at the Natural Resources Defense Council, which at the time was a small environmental group. Kennedy worked as a senior attorney for the council for about 28 years.

For his first project, he worked with an organization called Riverkeeper to help bring charges against polluters in the Hudson River Valley. He went on to help found the Waterkeeper Alliance, an environmental group that fights for clean water around the world. And he successfully fought to close a New York landfill that was contaminating water supplies and helped to defeat dams in Chile and Peru.

“If you took me back to when we worked together and you told me that this would happen in 2024, I would have been shocked,” said Liz Barratt-Brown, a senior adviser for the Natural Resources Defense Council who worked closely with Kennedy for years but lost touch with him about 10 years ago.

But now, she told me, she wasn’t shocked at all to see her former colleague support Trump.

“Am I gutted by this? Yes,” she added.

Drifting away

Barratt-Brown told me that Kennedy had drifted away from his colleagues in the environmental movement in the early 2000s, when he started spreading unfounded theories that linked vaccines to autism.

It was also around that time that he took a stand against many of his former allies in the environmental movement to protest a wind power project in Cape Cod, Mass. As Grist wrote at the time, he framed the debate as a clash between industry and wilderness, arguing that no one would consider building a wind farm in Yosemite National Park.

He left the Natural Resources Defense Council in 2014, around the same time his former colleagues said his embrace of anti-science views was becoming incompatible with the group’s work. But he didn’t stop claiming to defend environmental causes. In 2017, for example, when Trump was president, he denounced the administration’s policies to support coal and oil production, telling CNN that it was “hard to see a good end for our country from those kinds of policies.”

More recently, Kennedy has criticized the Biden administration’s environmental and climate policies, too. He said he would roll back the portion of Biden’s signature climate bill that funds carbon capture projects, arguing that they favor the fossil fuel industry.

He claimed to be the true environmentalist in the race, the candidate who would not focus just on climate change, which many conservatives still deny. He said he would give more attention to other environmental issues that were less divisive, such as soil regeneration and clean water.

As Friedman reported, while Kennedy said he wanted to help make food safer and healthier for Americans, the Trump administration approved more than 100 new pesticides that have been banned in other countries, often because of the risks they present to human health.

Kennedy didn’t mention environmental policy directly in his speech on Saturday, when he announced that he was supporting Trump. But he did say there were still “very serious differences” between him and the former president.

That day, before getting onstage, Kennedy told The Washington Post that he believed he could help sway Trump’s environmental policies. “I would hope to have an influence on how the environment is treated under his administration,” Kennedy said.

On Tuesday, Trump announced that Kennedy would be an honorary co-chair of his presidential transition team.

Asked for comment, Brian Hughes, a senior adviser to the Trump campaign, said in a statement that “we are proud” that Kennedy had “been added to the Trump/Vance transition team.”

His former allies in the environmental world are deeply skeptical. “Whatever delusional idea Kennedy might have about influencing Donald Trump to be better on environmental issues is as out of touch with reality as the other conspiracy theories he peddles,” said Sarah Burton, the national political director of the Sierra Club.

To Manish Bapna, the president of the N.R.D.C. Action Fund, the nonprofit group’s political arm, it wasn’t about delusion. “This looks like raw opportunism,” he said. “Someone desperately seeking relevance, whatever the cost.”

Will A.I. ruin the planet or save the planet?

The global experiment in artificial intelligence is just beginning. But the spending frenzy by big tech companies for building and leasing of data centers, the engine rooms for A.I., is well underway. They poured an estimated $105 billion last year into these vast, power-hungry facilities.

That spending spree is increasing demand for electricity and raising environmental concerns. A recent headline in The New Yorker called the energy demands of A.I. “obscene.” But there’s another perspective on A.I. and the environment, focusing not on how the technology is made but on what it can do.

A.I. has the potential to help accelerate scientific discovery and innovation in one field after another, lifting efficiency and reducing planet-warming carbon emissions in sectors like transportation, agriculture and energy production. Here’s what to know. — Steve Lohr.

Correction: The Climate Forward newsletter of Oct. 10, 2023, described incorrectly a study’s estimates of power consumption by A.I. servers. The analysis, in the journal Joule, estimated that, by 2027, A.I. servers manufactured that year alone could use between 85 to 134 terawatt hours annually. It did not estimate that all A.I. servers could consume that much power by 2027.

Thanks for being a subscriber.

Read past editions of the newsletter here.

If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, please consider recommending it to others. They can sign up here. Browse all of our subscriber-only newsletters here. And follow The New York Times on Instagram, Threads, Facebook and TikTok at @nytimes.

Reach us at climateforward@nytimes.com. We read every message, and reply to many!