With high demand for drugs like Ozempic, and a limited supply, a novel marketplace has emerged to cater to customers who can’t access them. Dozens of telehealth companies offer online prescriptions for cheaper, compounded versions of these medications. These alternative drugs come in vials, with syringes to draw out each dose, and cost hundreds of dollars less than brand-name options.

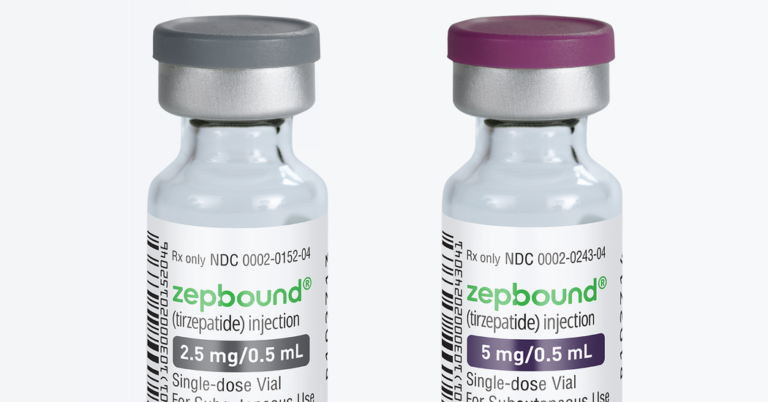

On Tuesday, Eli Lilly announced that it would start selling low doses of its weight-loss drug Zepbound in vials, too — at a far lower price than its pens, which come with pre-filled doses. These vials will be made available only through LillyDirect, a telehealth platform the company launched in January that connects patients with providers who can prescribe obesity drugs. Like compounded drugs prescribed by online startups, Zepbound vials can be delivered right to patients’ doors.

The lower-cost offering could expand access for the many people whose insurance plans do not cover the powerful weight-loss medication, said Lindsay Allen, a health economist at Northwestern Medicine. As weight-loss drugs have grown in popularity, some insurers have restricted access to them or stopped covering them altogether, to get ballooning costs under control. Some estimates suggest that millions of patients have in turn sought out cheaper alternatives to these drugs from compounding pharmacies, which can make copycat versions of any medication the Food and Drug Administration lists as “in shortage.” That includes tirzepatide, the substance in Zepbound and the diabetes drug Mounjaro.

Lilly’s announcement also presents a highly unusual challenge to the many telehealth companies now offering weight-loss drugs, and underscores the threat they pose to Lilly’s hold on the market, Dr. Allen and other experts said.

“Maybe this is a signal to that space: ‘We will get this market share back from you, even if it means lower pricing,’” said Dr. Timothy Mackey, a professor at the University of California, San Diego who has studied the counterfeit weight-loss drug market.

The vials are significantly cheaper than Zepbound pens, which cost just over $1,000 a month without insurance. A month’s supply of the 2.5-milligram dose will cost $399, and a month’s worth of the five-milligram dose will cost $549. The vials may benefit people who don’t have insurance coverage for Zepbound, including those on Medicare, said Patrik Jonsson, executive vice president of Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, a professor of pharmacology and physiology at Georgetown University Medical Center, said she was concerned about the appeal to people on Medicare, which has so far declined to cover medications strictly for weight loss. She noted the drugs come with unique risks for older patients, including a loss of muscle mass that may make people over 65 more likely to suffer fractures or become frail.

“Older people do not need to lose muscle,” she said.

Outside experts said the move could help Lilly regain customers who are currently getting compounded tirzepatide, which typically costs between roughly $250 and $450 a month.

Lilly is positioning its vials as a safer option than compounded drugs for people who cannot afford its pens. Compounded drugs are subject to far less oversight than traditionally approved medications, and health officials have repeatedly warned against taking compounded weight-loss drugs in particular.

“There is no reason why any single U.S. person should be on a non-F.D.A. approved medicine that is not controlled for safety, quality and effectiveness,” Mr. Jonsson said. “This is a way of just safeguarding the U.S. population.”

Lilly announced this month that all doses of tirzepatide were now available. The F.D.A. will have to review the supply before taking it off its shortage list.

“When we are off the shortage list, there should be no space for mass compounders,” Mr. Jonsson said. Lilly has already mounted legal challenges against compounding pharmacies.

In addition to connecting patients with providers, LillyDirect will also now allow patients with prescriptions from any doctor to purchase vials, needles and syringes directly from Lilly. Patients will have to self-pay for the drugs; Lilly will not accept insurance coverage for the vials. The company said it is able to offer what it called “transparent pricing” for the vials in part because it can sell the drug directly, “removing third-party supply chain entities,” according to a news release.

The company will offer vials with only the two lowest doses of Zepbound. Many patients stay on a five milligram dose, Mr. Jonsson said. But some gradually increase their dose, up to a maximum of 15 milligrams. Any patient interested in taking more than the five-milligram dose would have to transition to the pens.

For patients on the lower doses, though, the company is effectively undercutting itself by offering a cheaper alternative to its own medication. Mr. Jonsson acknowledged that it was “likely” that patients paying out of pocket for Zepbound pens would switch to the cheaper vials. “Is that going to be 10 percent? 60 percent? We don’t know,” he said.