One day after launching a Starship rocket on a dramatic test flight in Texas, SpaceX readied a Falcon Heavy rocket for launch Monday from Florida to send a $5.2 billion NASA probe on a 1.8-billion-mile voyage to Jupiter to find out if one of its moons hosts a habitable sub-surface ocean.

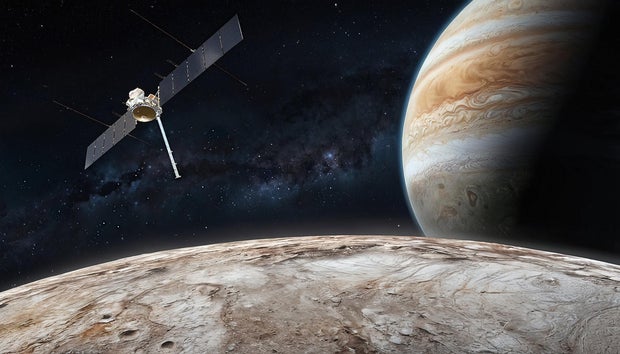

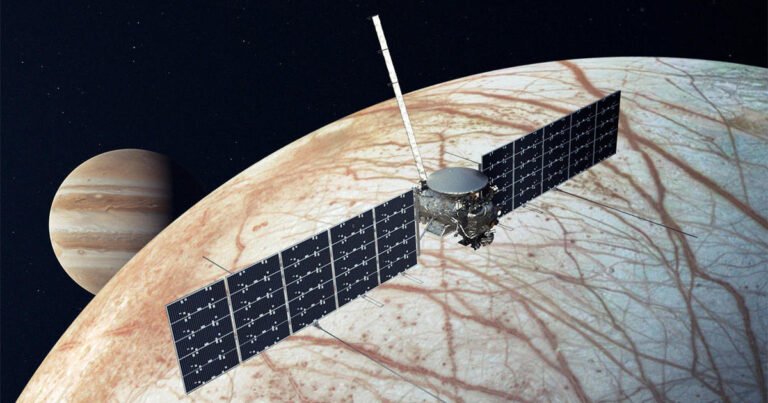

If all goes well, the Europa Clipper will brake into orbit around Jupiter in April 2030, setting up 49 close flybys of the frigid moon Europa, an ice covered world with an interior warmed by the relentless squeezing of Jupiter’s gravity as it swings around the giant planet in a slightly elliptical orbit.

NASA

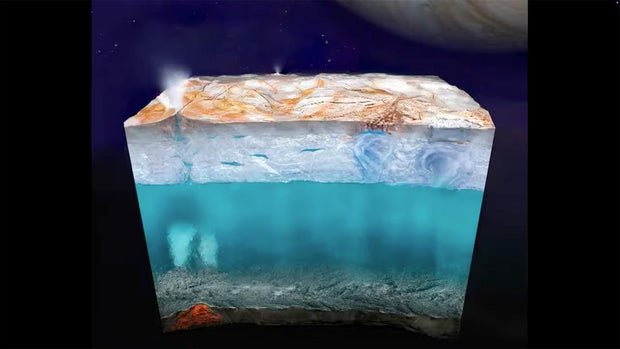

Data from previous missions and long-range studies from Earth indicate a vast salt-water ocean lurks beneath the moon’s frozen crust, providing a possibly habitable environment. Whether microbial life exists in that ocean is unknown, but the Europa Clipper’s instruments will try to find out if it’s at least possible.

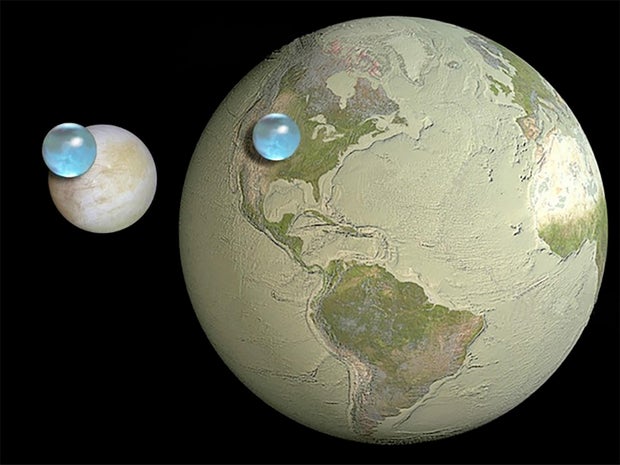

“Europa is an ice covered moon of Jupiter, about the size of Earth’s moon, but believed to have a global subsurface ocean that contains more than twice the water of all of Earth’s oceans combined,” said Project Scientist Robert Pappalardo.

“We want to determine whether Europa has the potential to support simple life in the deep ocean, beneath its icy layer,” he said. “We want to understand whether Europa has the key ingredients to support life in its ocean, the right chemical elements and an energy source for life.”

NASA originally planned to launch the Clipper last week, but mission managers ordered a delay to avoid Hurricane Milton, which swept across Cape Canaveral on Thursday. An additional one-day slip was ordered to resolve a technical issue and while details were not provided, the rocket was cleared for launch.

Liftoff from historic pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center was targeted for 12:06 p.m. EDT Monday. Generating more than 5 million pounds of thrust, the triple-core Falcon Heavy, the most powerful operational rocket in the SpaceX inventory, will boost the 12,800-pound Europa Clipper to the velocity needed to break free of Earth’s gravity.

While SpaceX normally recovers first stage boosters for refurbishment and reuse, all three core boosters and the rocket’s second stage will use all of their propellants to accelerate the Clipper to the required Earth-departure velocity. As such, no first stage recoveries are possible.

“Falcon Heavy is giving Europa Clipper its all, sending the spacecraft to the farthest destination we’ve ever sent, which means the mission requires the maximum performance. So we won’t be recovering the boosters,” said Julianna Scheiman, SpaceX director of NASA science missions.

“I don’t know about you guys, but I can’t think of a better mission to sacrifice boosters for where we might have an opportunity to discover life in our own solar system.”

To get to Jupiter, the Clipper will first fly past Mars on March 1, using the red planet’s gravity to boost its speed and bend the trajectory to send the probe back toward Earth for another gravity-assist flyby in December 2026. That will finally put the Clipper on course for Jupiter.

NASA

If all goes well, the probe will brake into orbit around Jupiter on April 11, 2030, using the gravity of the moon Ganymede to slow down before a six- to seven-hour firing of the probe’s thrusters. The first of 49 planned flybys of Europa, some as low as 16 miles above the surface, will begin in early 2031.

The mission is expected to last at least three years with the possibility of an extension depending on the spacecraft’s health.

In either case, the Clipper will end its voyage with a kamikaze descent to Jupiter’s moon Ganymede to prevent any chance of a future uncontrolled crash on Europa that might bring earthly microbes to the moon and its possibly habitable sub-surface environment.

“The spacecraft faces some big challenges,” Pappalardo said. “The distance of Jupiter is five times farther from the sun than the Earth is. That means it’s very cold out there, and there’s only faint sunlight to power the solar arrays. So they’re huge.”

Once deployed, the 13.5-foot-wide solar arrays will stretch more than 100 feet from end to end — more than the length of a basketball court — with two radar antennas extending 58 feet from each array.

Power requirements aside, Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field “acts like a giant particle accelerator at Europa,” he said. “A human would receive a lethal dose of radiation in just a few minutes to a few hours, if exposed to that environment.”

The Clipper was designed to withstand repeated doses of extreme radiation while making close flybys of Europa, housing its flight computer and other especially sensitive gear inside a vault shielded by sheets of aluminum-zinc alloy.

But engineers were dismayed to discover earlier this year that critical electrical components used throughout the spacecraft failed at lower levels of radiation than expected.

Engineers and managers held a major review to determine how that might affect the Clipper and eventually concluded the spacecraft could minimize radiation-induced degradation by slightly changing the way the flybys are executed. The only alternative was to delay the launch for several years to replace the suspect components.

Mission scientists were eager to finally get the long-awaited mission underway.

“What would be the greatest outcome? To me, it would be to find some sort of oasis, if you like, on Europa where there’s evidence of liquid water not far below the surface, evidence of organics on the surface,” Pappalardo said. “In the future, maybe NASA could send a lander to scoop down below the surface and literally search for signs of life.”

NASA

As for what sort of life might be possible below the moon’s frozen surface, “we’re really talking simple, like single-celled organisms,” he said. “We don’t expect a lot of energy for life in Europa’s ocean like we do here on the surface of Earth.

“So we don’t expect fishes and whales and that kind of thing,” he added. “But we’re interested in could Europa support simple life, single-celled organisms?”

The Clipper is equipped with nine state-of-the-art instruments, including narrow- and wide-angle visible light cameras that will map about 90% of Europa’s surface, imaging details down to the size of a car. An infrared camera that will look for warmer regions where water may be closer to the surface or even spewing into space.

“The cameras will observe over 90% of Europa’s surface at a resolution of less than 100 meters to a pixel, or 325 feet,” said Cynthia Phillips, a project staff scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “That’s about the size of a city block.

“The narrow-angle camera will be able to take pictures at a resolution as high as half a meter per pixel. That’s about 1.6 feet. And so it will be able to see car-sized objects on the surface of Europa.”

Two spectrometers will study surface chemistry and the composition of the moon’s ultra-thin atmosphere, on the lookout for signs of water plumes and other ocean-driven features. Two magnetometers will probe the sub-surface ocean by studying electrical currents induced by Jupiter’s magnetic field.

An ice-penetrating radar will “see” up to 19 miles beneath the icy crust to look for pockets of water in the ice and helping scientists understand how the ice and water interact with the presumed ocean.

“Those signals will penetrate through into the subsurface, where they may be able to bounce off a liquid water layer, such as a lake within the icy shell, or maybe even penetrate all the way through, depending on how thick the surface ice layer is and other factors, such as its structure and composition,” Phillips said.

“The radar could be able to penetrate as deep as 30 kilometers. That’s about 19 miles below the surface.”

Two other instruments will study gas and dust particles on the surface and suspended in the atmosphere to analyze their chemical makeup. Finally, scientists will measure tiny changes in the probe’s trajectory, allowing them to glean details about Europa’s internal structure.

“We know of our Earth as an ocean world, but Europa is representative of a new class of ocean worlds, icy worlds in the distant outer solar system where saltwater oceans might exist under their icy surfaces,” Pappalardo said. “In fact, icy ocean worlds could be the most common habitat for life, not just in our solar system, but throughout the universe.

“Europa Clipper will, for the first time, explore such a world in depth. … We’re at the threshold of a new era of exploration. We’ve been working on this mission for so long. We’re going to learn how common or rare habitable icy worlds may be.”