Jasmine Banks’s disillusionment started with a credit-card bill.

She was proudly, fervently dedicated to the radical mission of the nonprofit where she worked, that police everywhere should be abolished. She reported to the group’s founder, a charismatic activist with a compelling life story: His fiancé had been killed by an abusive cop. She believed their nonprofit would show the world it did not need law enforcement.

Then her boss went on vacation, and left her, as deputy director, in charge. Sitting at her desk at home, she saw in the accounting system that he had just used the nonprofit’s card to pay a $1,536 hotel bill — a big bill for such a small organization.

At first, she was not worried, just curious. Why would he do that?

“He knows we’re running out of money,” Ms. Banks remembered thinking.

She dug deeper into the nonprofit’s bank records and found much more that concerned her. Mansion rentals. Vet bills. Luxury clothes. Finally, a stay at a Cancun resort. Ms. Banks scrolled back through Facebook to the week that resort bill was paid. She saw her boss, Brandon D. Anderson, posing in a pool.

The photo was tagged: “Cancun.”

She stewed for a few days, then sent an email to members of the nonprofit’s board: “I am reaching out to you regarding a confidential issue that requires immediate attention.”

What happened next tested everyone who had believed in Mr. Anderson’s vision — fueled by his story of personal pain — for the transformation of America’s relationship with police. Because of what their captivating leader had done, Ms. Banks and her colleagues were forced to grapple with their most deeply held ideals about altruism, crime and justice.

Mr. Anderson appeared to have misused the group’s funds — an allegation he denies. And as a result, the employees lost their jobs — and a chance to build a different world.

They were left with a painful dilemma. They thought the law had been broken, and wanted justice. But they had sworn never to call the authorities on anyone.

An App for That

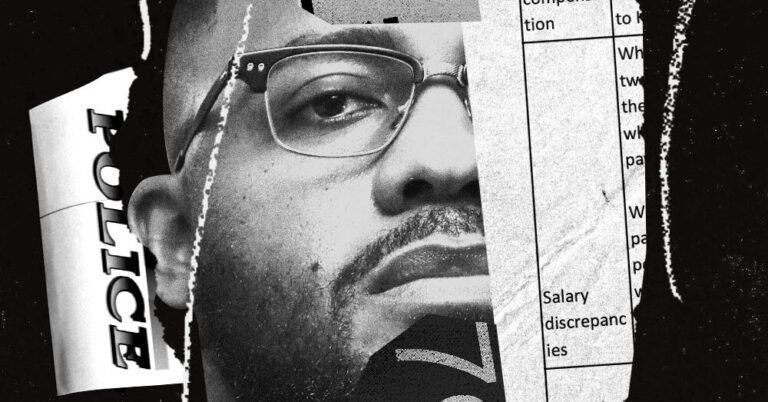

Mr. Anderson, 39, a handsome man with retro browline glasses and a touch of gray in his beard, has the look and optimistic tone of a Silicon Valley founder. His nonprofit was relatively small, taking in about $4.4 million over its lifetime, but his searing story gave him — and his group — an outsize profile.

Over the years, Mr. Anderson has told that story in countless interviews and public appearances, many of which were recorded, and in meetings with potential donors. He told them he had left Oklahoma City to join the Army at 18, serving two stints in Iraq. After that, he graduated from Georgetown University in 2015.

But often, Mr. Anderson began his story with what he had lost: “this tall, skinny, bigheaded Black boy I first met in third grade.”

“Falling in love with him was like falling asleep in class,” Mr. Anderson once told an audience. “It’s not something I meant to do. It’s just something that happened.”

Mr. Anderson said the two of them ran away from home together at about 15, and Mr. Anderson sold drugs to survive. They squatted in an abandoned home on the outskirts of Oklahoma City — two Black teenagers in a world with little tolerance for them or their love.

“In 2006, he asked me to marry him,” Mr. Anderson said. “It was the happiest day of my life.”

Then, he said, while Mr. Anderson was away in the Army in 2007, his partner was slain by Oklahoma City police.

“He was driving a car that the officer said was stolen. The car had never been stolen. In fact, it was the car that me and my partner had saved up to buy,” he said in one interview. “My partner’s death threw me into two years of clinical depression. The loss of my partner — the killing of my partner — by the police changed my life forever.”

Mr. Anderson said the officer involved had long been abusive, but that nobody had ever filed an official complaint against him, because either the process was too cumbersome or they feared retaliation.

It was a flaw in the system. To fix it, Mr. Anderson founded a nonprofit in 2017. Its mission: to build a website that would let people file complaints against police from their phone.

“We connect you to a free lawyer, file a complaint against the officer and use your story to lobby for policies that defund police and invest in your community,” Mr. Anderson said.

He called the nonprofit Raheem AI. Where did the name come from?

“It’s named after my partner,” he said.

Racial Justice Commitments

Other groups were already working to fix broken police complaint systems. But their efforts were largely local ones, grinding out change slowly, one department at a time.

Mr. Anderson proposed an easy national fix, and he could claim a deep personal connection to the problem.

Cat Brooks, co-founder of a group called the Anti Police-Terror Project and a longtime activist in Oakland, where Mr. Anderson moved around 2019, began introducing him to her like-minded network. “I looked at him as this young organizer that I was bringing into our movement,” Ms. Brooks said.

Mr. Anderson was profiled in the media, featured at a TED conference, and recognized by a chapter of My Brother’s Keeper, a part of the Obama Foundation.

Then, in 2020, the murder of George Floyd brought renewed attention to abuses by police and led to an sharp increase in giving to nonprofits focused on criminal-justice reforms. Mr. Anderson’s organization got a share of the surge. It received $1.6 million in donations from tech-focused charities and huge nonprofits like the Kresge and Annenberg foundations.

Nonetheless, Mr. Anderson’s complaint system — “Yelp for police,” he called it — did not work. His website collected more than 2,700 stories from users about their interactions with police — accounts of unjustified traffic stops, physical assaults and harassment. But the work had little impact because Raheem was unable to solve a mind-bending technical problem.

There are 18,000 police departments in America. Some accept complaints online, but many require people to make a phone call or go to a police station. Raheem failed because it never offered a one-stop way for users to file their complaints directly with police.

But the organization still had money, and Mr. Anderson still had access to it. In early 2021, he used its funds to go on a shopping spree.

He spent $2,000 at Bloomingdale’s. Then $2,800 at Bottega Veneta, an upscale Italian clothing store. After that: Saks, Alexander McQueen, and the online luxury-goods store Farfetch.

In all, Mr. Anderson spent $11,000 in charity money on clothing that year, according to financial records. In those spending records, the purchases were all marked “Executive Director clothing allowance” or “Clothes for E.D.”

One employee, who later resigned, questioned these charges at the time, and Mr. Anderson said that the group’s board had approved them, according to a copy of the employee’s exit interview obtained by The New York Times.

But all three members of the nonprofit’s board of directors for that year told The Times they had not approved any clothing allowance — and would not have. It was a poor use of charity money, they said, especially since everyone at the nonprofit worked remotely from home.

“No, no, no. Categorically, no. Not in a million years,” said Phillip Agnew, a board member at the time who runs a liberal political group called Black Men Build.

Then came an immensely frustrating moment in the broader effort to change police behavior. Activists had spent years pushing for better training and accountability for police killings, such as that of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014, only to see the numbers of such fatalities keep rising. Then they saw Mr. Floyd murdered on video, in daylight.

In response, some philanthropists sought to fund more radical ideas. They wanted a world without police — or, at least, with far fewer of them.

In 2021, Mr. Anderson declared that Raheem AI’s plan for a one-stop complaint site — the thing it had long promised and never delivered — had actually been a mistake. Gathering complaints was pointless. Police could never be fixed.

“Reform doesn’t make us safer: it sustains police terror,” the group announced.

Now, as it happened, Mr. Anderson said he was building a new app that would help lessen the need for police.

Cities and nonprofits at that time were experimenting with “alternative first responders.”

These might be medics, social workers or psychologists. They could be dispatched through the 911 system instead of police in response to calls about people in mental distress, or sleeping outside, or using drugs. The idea was to lower police workload and reduce the risk of a fatal encounter.

As before, Mr. Anderson told donors that he could take this very real — but localized — movement and supersize it to a national solution.

He said he would build a network of alternative responders and “liberated dispatchers” to take calls and send them out. The system would run on a new app.

“Essentially, it’s an alternative dispatching system to 911,” he said.

This idea made the complaint app look almost simple by comparison.

To work properly, this app would need to triage calls and assign the right responders. If a call escalated, the system would have to assess if police were needed after all. If callers could not identify where they were, or if they were somewhere unreachable, that too would need to be overcome.

“I can’t even begin to think about the level of complexity,” said Tahir Duckett, who leads a center at Georgetown that provides technical assistance to these alternative programs.

“Why not just use 911?” Mr. Duckett said. “People on the street already know 911.”

Despite those challenges — and the failure of Mr. Anderson’s previous app — donors gave more than $1.3 million to this effort.

The Michigan-based Kresge Foundation, one of the richest in the country, had given $220,000 to Raheem AI under its original mission. Now, Kresge pledged $675,000 to the new idea, listing Raheem among 59 groups it selected for “racial justice commitments.”

Why fund this group again rather than one with a better track record? The Kresge Foundation responded by saying that it had never expected Mr. Anderson to meet any specific goals.

Support to Raheem “did not come with expectations of meeting project deliverables,” spokeswoman Christine Jacobs wrote in an email message.

With this cash infusion, Raheem AI hired several other police abolitionists.

The Burden of Context

One of them was Ms. Banks, 38, a mother of four who had recently moved from Arkansas to Washington, D.C., and had spent her career working for liberal nonprofits with tiny budgets. She had formed her views on police both from personal experience — as a child, she said, she was held in a police station break room after cops arrested her mother for driving with an expired license plate — and from nationally publicized events like Mr. Floyd’s death.

In her view, the country’s approach to law enforcement was too corrupted by racism and wealthy interests to offer true justice. She could only hope that the system would be replaced by something better, eventually.

Then she saw Mr. Anderson’s approach, which told donors that a better system was just an app away. “I was just sort of astounded,” she said, to see how easily Mr. Anderson raised money.

Despite his fund-raising prowess, he also often warned employees that they were running short of money and that layoffs might be imminent.

The work stalled.

Employees found Mr. Anderson increasingly hard to reach. When they did, he could not express how he would make his plan work.

“He would say that’s why he hired smart people, so we could tell him,” Ms. Banks said.

Then she found the hotel bill, and notified members of the board.

At that point, the board consisted of Mr. Anderson and two independent members. It was those two that Ms. Banks contacted. They investigated and questioned more than $250,000 in charges since 2021 alone, internal documents show.

Among them: Mr. Anderson — who was paid a salary of $160,000 — had spent $1,500 of the charity’s money at a chiropractor; $5,000 on veterinary care; and an astounding $46,000 on ride-share services like Uber and Lyft. Most confoundingly, the nonprofit had paid $80,000 for luxury vacation rentals, including a service that let members stay in luxury mansions around the world, according to the board’s accounting.

One of the two independent board members, a civil rights activist named Samuel Sinyangwe, said that Mr. Anderson had explanations for some of the charges. The mansion rental and Uber charges were for work-related travel, the chiropractor was necessary medical care and the veterinary bills were paid back.

But he asked for more time to provide proof, Mr. Sinyangwe said.

The two independent board members put Mr. Anderson on leave. But when they disagreed about whether Mr. Anderson should be immediately fired, both ended up resigning over the deadlock.

Only one board member remained: Mr. Anderson.

The Times called Mr. Anderson’s cellphone and left messages seeking an interview with him. A reporter followed up with an emailed list of detailed questions about Raheem AI’s operations and the allegations that Mr. Anderson had misused its money. Federal law prohibits nonprofit executives from diverting their charity’s money for their own use.

Mr. Anderson declined to answer the detailed questions. He sent a written statement saying that some allegations made about him were “rife with untruths,” but declined to specify which.

“It’s easy to assign failure to one cause or another in hindsight, and individual expenditures are easy to mischaracterize without the burden of context,” he said in the statement. “The bottom line is simply that it didn’t work, and as the leader of that effort I share most of the blame.”

For now, his nonprofit appears legally active, but functionally dead. Several donors pulled their funding.

Three employees were left out of work.

A Search for Raheem

This spring, as the nonprofit unraveled, employees and former board members also began to look into the back story that Mr. Anderson told about how he became an activist: the death of his partner in Oklahoma in 2007.

Raheem had been the inspiration for the whole organization. But who was he, and why didn’t anyone know more about him?

Seeking to verify his account, The Times examined records kept by the Oklahoma state medical examiner and the Tulsa World news organization, which has tracked police killings in the state since 2007. The Times found no evidence of the killing that Mr. Anderson has described. No homicide in the entire state of Oklahoma involved a man named Raheem, nor did any match the particulars of the officer-involved death Mr. Brandon had described.

However, Mr. Anderson himself did at have least one run-in with the police. A Times reporter found an arrest record for Mr. Anderson in the District of Columbia, where Mr. Anderson lived while attending Georgetown. In 2014, Mr. Anderson was charged with simple assault after allegedly pushing his then-boyfriend against a wall during an argument. The charge was later dropped.

Ms. Brooks, the longtime activist who had brought Mr. Anderson into the anti-police-brutality movement in Oakland, said she realized something in hindsight.

“He wouldn’t engage with other impacted family members. I would invite him all the time, and he just wouldn’t do it,” she said.

Once, she said, she invited him to join 25 families in comforting another that had just lost a relative to police. The others went inside the house. Mr. Anderson stayed on the porch, she said. She suspects now that he did not feel comfortable because he did not actually share their experience.

“It hurts my heart to say it, but I think it was a con from the beginning,” Ms. Brooks said.

As bitter as the experience was, the nonprofit’s former employees believed they should not report Mr. Anderson to any government authority.

Instead, they hoped for other forms of accountability. Perhaps they could shame him into taking responsibility. Maybe he’d just face bad karma.

They said justice would not — could not — come from law enforcement.

“Brandon is a masculine-presenting Black person. And the way that police treat masculine-presenting Black people is terrible,” said Nancy Mariano, who had been a software engineer at the nonprofit.

“Even if Brandon committed a crime, I don’t want Brandon to die,” Ms. Mariano said. “So I don’t want to put Brandon in that position.”

Still, Ms. Mariano said, that decision came with a feeling of powerlessness: “This is the perfect crime.”

Ms. Banks, who pulled the loose thread that started the unraveling, felt that way too.

Then she reconsidered. She decided she wanted to get her unpaid back wages, so she emailed the District of Columbia’s attorney general — a local regulator who handles employee disputes. The nonprofit was still registered in D.C., where Mr. Anderson had founded it before leaving for Oakland. In her reasoning, she was not calling the law. She was calling for help.

Then the law emailed back.

Her case had been referred to another part of the attorney general’s office that investigates nonprofit fraud. It can bring civil lawsuits or refer a case for criminal prosecution.

Those investigators wanted documents that she had.

It had bothered Ms. Banks that Mr. Anderson had escaped any reckoning for what he had done. Here was that chance for accountability.

She handed over the documents.

“Do I have personal guilt? That’s an interesting question,” she said, and paused for a long time. “No.”

Usually I do not read article on blogs however I would like to say that this writeup very compelled me to take a look at and do it Your writing style has been amazed me Thank you very nice article