Phil Donahue, who died on Sunday at age 88, will long be remembered as the king of daytime television.

Starting in 1967 at a local Ohio station, he immediately set a new tone for what a talk show could be by tackling some of the most taboo topics of the day. His unique approach, which included making audience participation fundamental, proved wildly successful, and over the next 29 years, he would record more than 6,000 episodes of “The Phil Donahue Show” — shortened to “Donahue” during his heyday in the late 1970s and ’80s.

He was such a juggernaut that in Oprah Winfrey’s early days, she was told it would be impossible to compete. In an Instagram post on Monday that included a glitzy black-and-white photo of them together, Winfrey said, “There wouldn’t have been an Oprah Show without Phil Donahue being the first to prove that daytime talk and women watching should be taken seriously.”

In a lengthy 2001 interview with the Television Academy, Donahue said he struggled the most with questions like, “Who was your best guest?” These questions are easy to ask but impossible to answer, he said.

Even if Donahue himself was loath to pick the most memorable moments, some episodes do stand out from the pack. Here are three that explain how he endured.

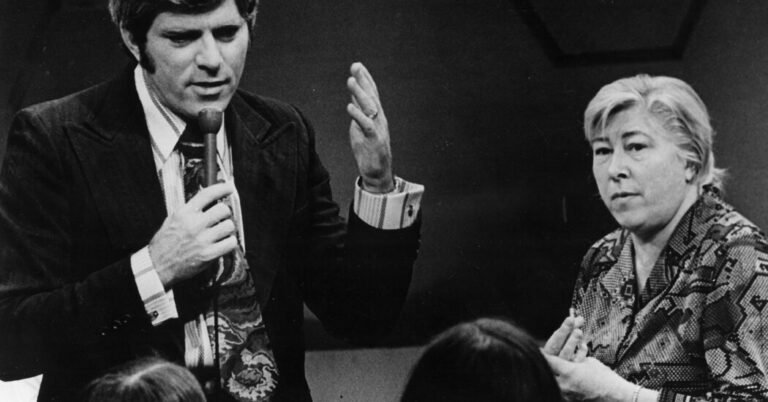

Madalyn Murray O’Hair

In his very first episode — which aired at 10:30 a.m. on Nov. 6, 1967, on WLWD-TV in Dayton, Ohio — Donahue interviewed one of the most hated figures in America: the atheist activist Madalyn Murray O’Hair, who had a significant role in the Supreme Court’s 1963 decision to ban compulsory prayer in public schools.

“Honest to goodness, I didn’t think I was going to be able to get out of the building,” Donahue, reminiscing on that first episode, said in that 2001 interview. “Can you imagine? People went berserk.”

He knew from the start, he said, that his show would need to bring a different energy to the screen. “We knew if we had any chance to succeed, we couldn’t be talking about juvenile delinquency or all these broad, very imprecise issues that are often discussed at rotary club meetings and other places,” he said. “We knew we had to have personalities who moved you to go to that phone and make a phone call.”

And call they did. During that first episode, the lines were so overwhelmed in Dayton that part of the phone system was paralyzed, Donahue said.

AIDS Education in the Early Days

In November 1982, Donahue used his show to elevate a quickly growing and widely misunderstood illness called AIDS, making him among the first to discuss the crisis on a public stage.

Instead of adding to the early fearmongering and confusion of the time, he set out to inform his audience about the then mysterious ailment by interviewing Philip Lanzaratta, who had AIDS; Dr. Dan William, who practiced in New York and diagnosed AIDS patients; and Larry Kramer, a screenwriter who helped found Gay Men’s Health Crisis and who had at that point already lost 17 close friends to AIDS.

“We’re two years into this illness now, and I’d venture to say that most of your audience still hasn’t heard about it,” Kramer said.

The episode, which was filmed in Chicago, tackled the crisis from numerous angles. Donahue and his guests, sitting around a table onstage, addressed the increasing number of cases; high-risk groups; symptoms and medical treatments; the possibility that a virus might be causing AIDS; the gay community’s response; and discrimination against gay people.

“Let’s make this point,” Donahue said early in the broadcast. “When the gay community has a problem, it does not get immediate, enthusiastic establishment support for whatever might ail it. We do live in a homophobic nation.”

Antiwar and Outspoken

In March 1991, in one of a handful of episodes Donahue did about the Persian Gulf war — an unusual move for a daytime show of the time — he interviewed the Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Peter Arnett. Arnett, who then worked for CNN, had recently returned from Iraq, where his dispatches were widely watched by the American public.

In the sprawling conversation, Donahue pressed Arnett on many sensitive topics including why Arnett reportedly would not let other reporters use his phone line out of Baghdad. Donahue asked Arnett for his views on the bombing by the U.S. military of what some believed was a baby milk factory, a notable moment in the war.

According to Entertainment Weekly at the time, the “Donahue” producer Deborah Harwick said, “We felt it was our obligation to educate our audience about the war.”

In 2002, Donahue tried to rekindle his talk show career with a nightly program on MSNBC. Barely six months in, it was canceled by the network for what it called flagging ratings. Donahue maintained that it was his antiwar perspective and his opposition to the looming war in Iraq that cost him the job.